(02 Falling)

Falling

What — To what extent is nature still nature when it has continued to be exploited by humans? This interactive scheme is an explication of the human interventions on the site of the Niagara Falls.

Where — Niagara Falls, Ontario 2009

Thus always does history, whether of marsh or market place, end in paradox. The ultimate value in these marshes is wildness and the crane is wildness incarnate. But all conversation of wildness is self-defeating, for to cherish we must see and fondle, and when enough have seen and fondled, there is no wildness left to cherish.

– A. Leopold (A Sand County Almanac, 1968)

On Power and Beauty

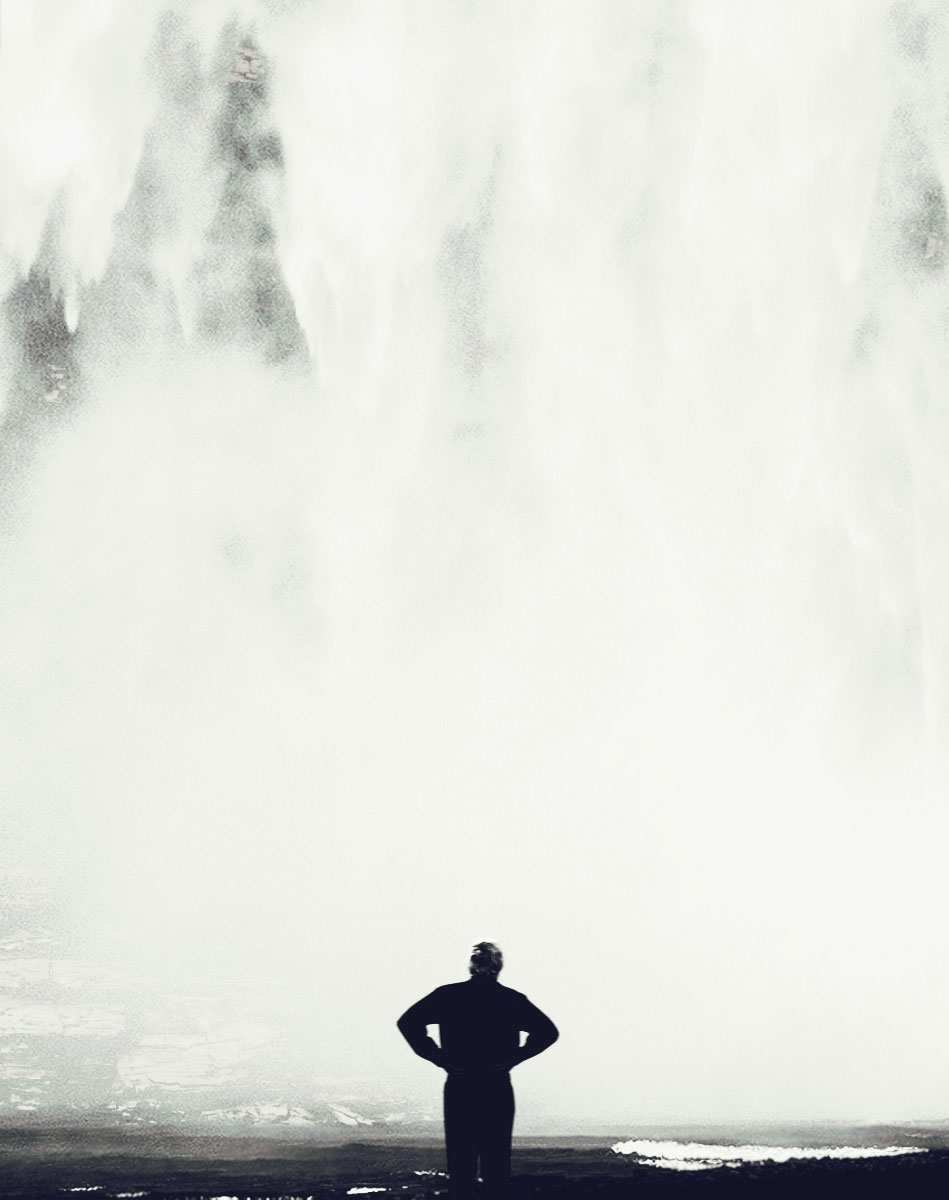

The unveiling of an artifice behind a “natural” wonder may result in a sublime confrontation; but can we still understand this moment as sublime when we are made aware of its artifice? Historically, the Niagara Falls has had a turbulent relationship with humans – the moment we were captivated by it, we wanted more from it. We have managed to manipulate, reconstruct and harness this “natural wonder”, most notably through the discreet diversion of the water for power generation and through cosmetic management and reconstruction for purposes of tourism.

Given the task to redesign the existing Niagara Falls tourist centre, I used this opportunity to explore the "nature" of this extraordinary site through these two modes of human intervention. We have had a detached relationship with the massive infrastructures we build, which have become the foundations to our modern existence. With the flick of a switch, the turn of a knob, we immediately have access to electricity and water. Intrinsic to the design of modern infrastructural systems is to hide them behind more polished surfaces. We are thus consistently shielded from the enormity of infrastructural intervention on the natural world. Similarly, we are shielded from the amount of environmental degradation that has occurred for the sake of upholding the image of nature. From dynamiting cliff rock edges to smoothing out the surface of Niagara's falling water, nature tourism can be likened to that of show business. It became my focus, then, for tourists to confront these once implicit interventions by way of being directly engaged in their processes.

A Network of Critical Tourism

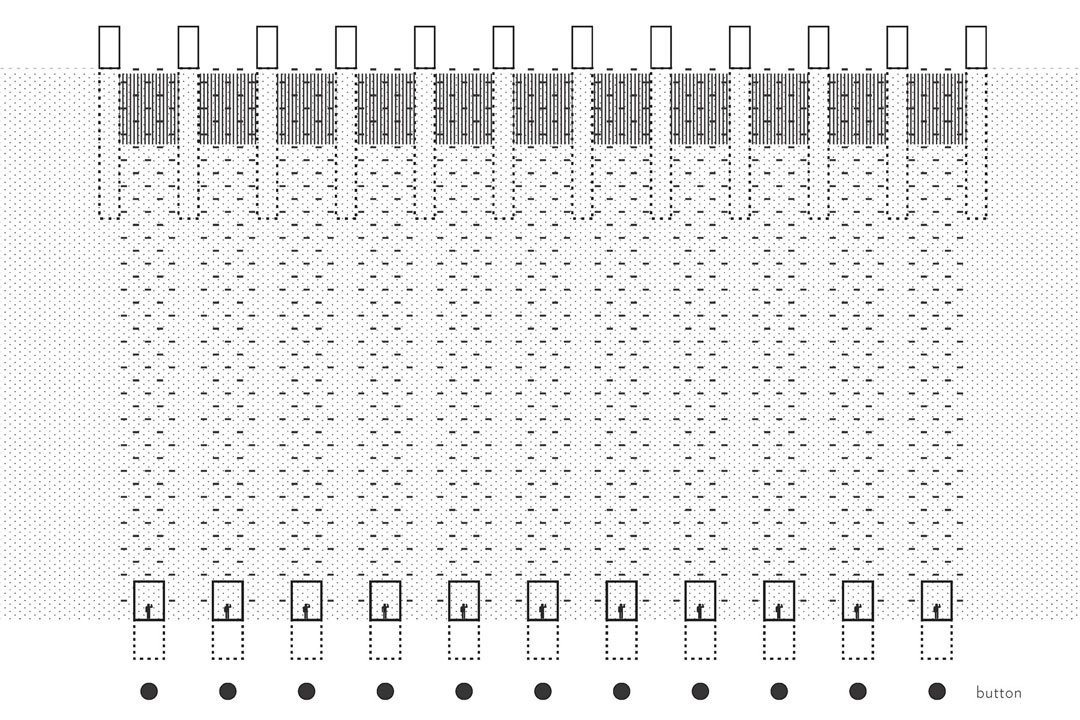

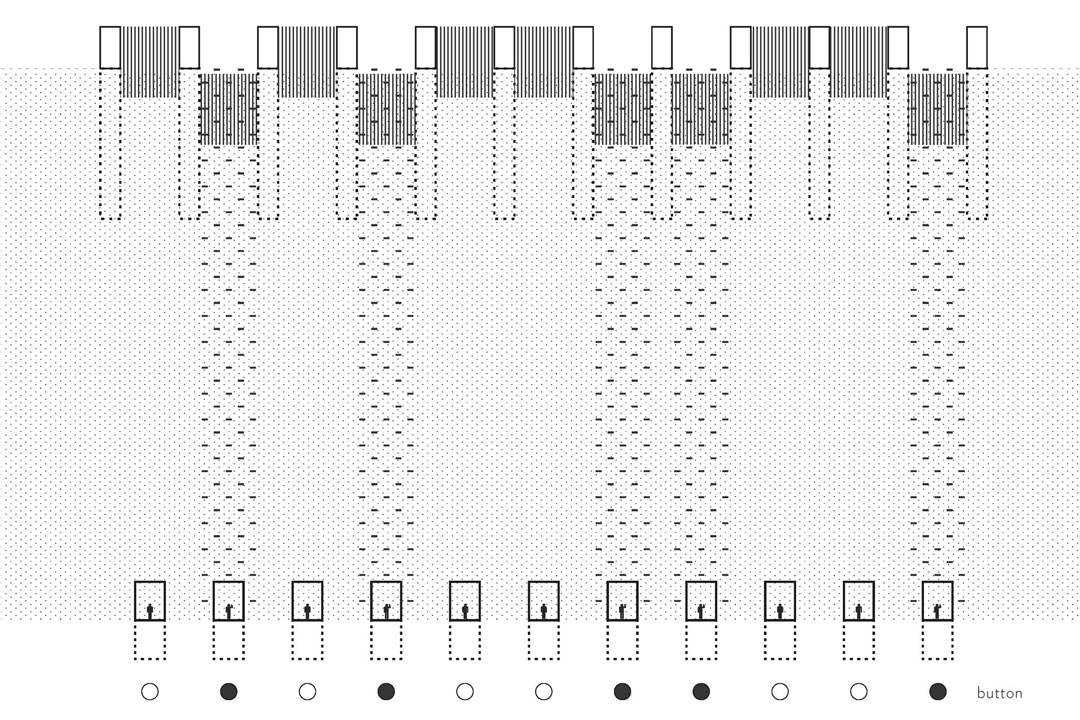

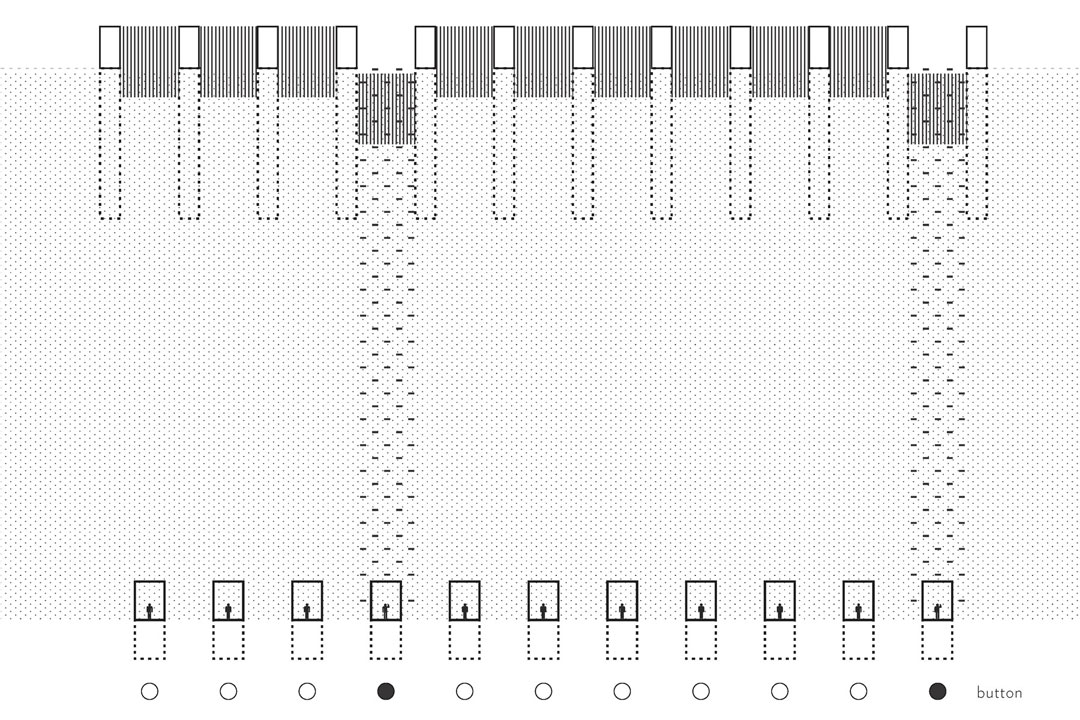

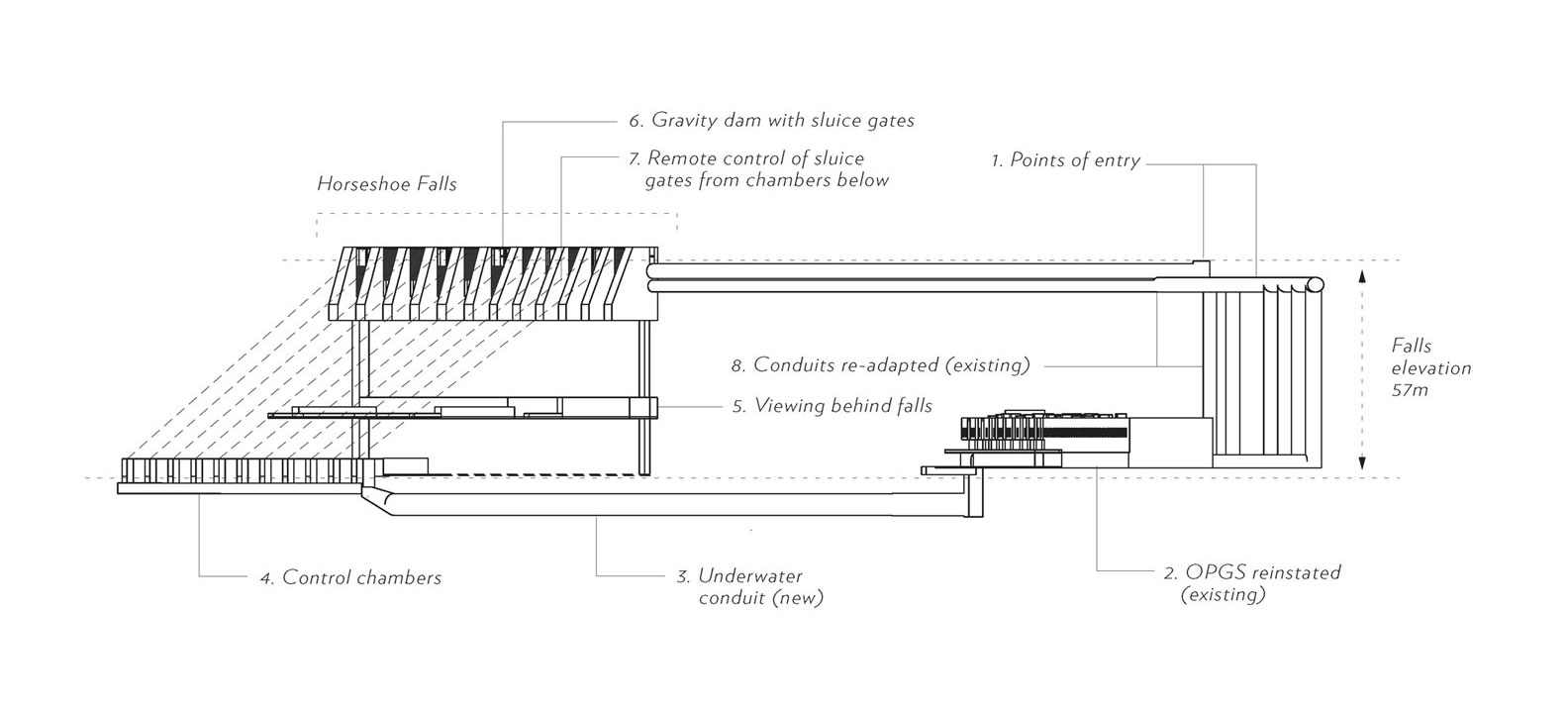

The proposal is a visible, large-scale loop of old and new, inhabitable and operable, infrastructure for purposes of tourism. It not only exposes existing infrastructures; it continues to exploit the site through the creation of additional structures. The four major components of the network include: A new power-generating Gravity Dam created to occupy the top edge of the Horseshoe Falls; the decommissioned Ontario Power Generation Station (OPGS) at the bottom west side of the falls, reinstated as a power station; a new set of Control Chambers at the foot of the falls, facing the gravity dam; old and new conduits (approx. 5m diameter) for water diversion and pedestrian connection.

This scheme grants tourists the ability to control the falling water in front of them with a push of a button – "on" or "off". This happens when a tourist finds their way to a control chamber where he/she is positioned in front of the waterfall and decides whether or not to remotely activate the corresponding dam sluice gate at the top of the falls. If activated, the sluice gate comes down, diverting the water towards the OPGS below via conduits; the tourist watches the falling water disappear before their eyes and will be confronted, instead, with rock face. The diverted water is generated into power and made visible at the generation station and at various points along the network indicating the gates that have been activated. Tourists occupying different locations along the network experience the striking effects of pushing the button in their respective locations: Those in the OPGS are witness to the process of power generation as corresponding turbines are activated in front of them, while tourists occupying the gravity dam are witness to the massive gates rising and falling in front of them, and the rush of water diverting below them.

This scheme can be seen as an explicit display – a hyperbolic re-enactment of what has already occurred. It would undoubtedly require substantial environmental upheaval for its construction; the underlying difference is that these processes of upheaval and control over the environment are made tangible in a way that can no longer be denied.