(01 Urban Informality)

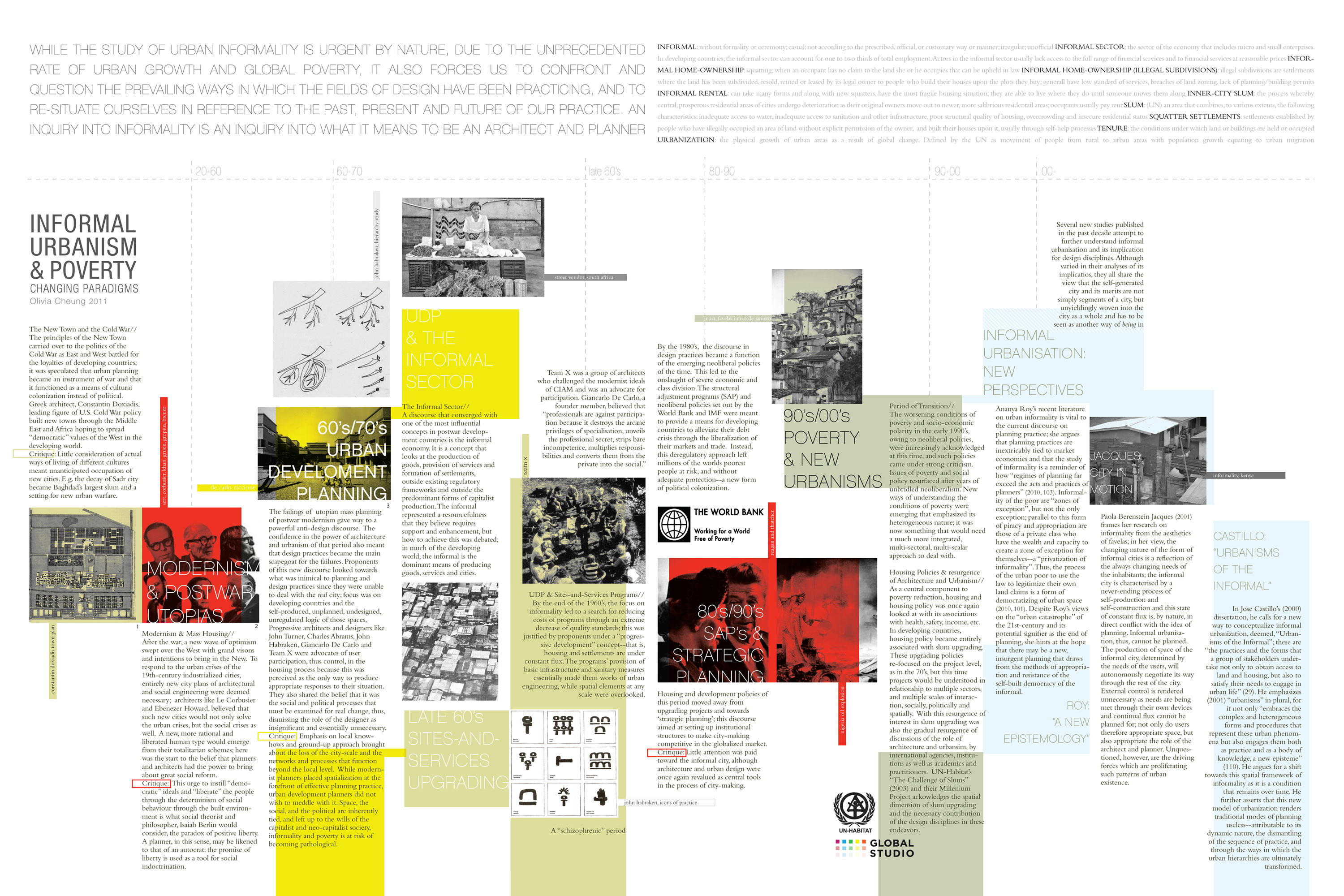

Urban Informality: Changing Paradigms

The following is an excerpt from a research study (2012), which traces and analyzes the changing paradigms of urban informality in relation to poverty and planning practices from a global political perspective. The intent was to gain a broad understanding of a phenomena that is in direct opposition to the conventions of architecture and planning practice, yet is one of the globe's most extensive forms of spatial practice. It is a way of life to those who have had little to no means of participating in the ever-exclusionary economic world systems, and it forces us to confront the ways in which we have been practicing: An inquiry into informality is an inquiry into what it means to be an architect and planner.

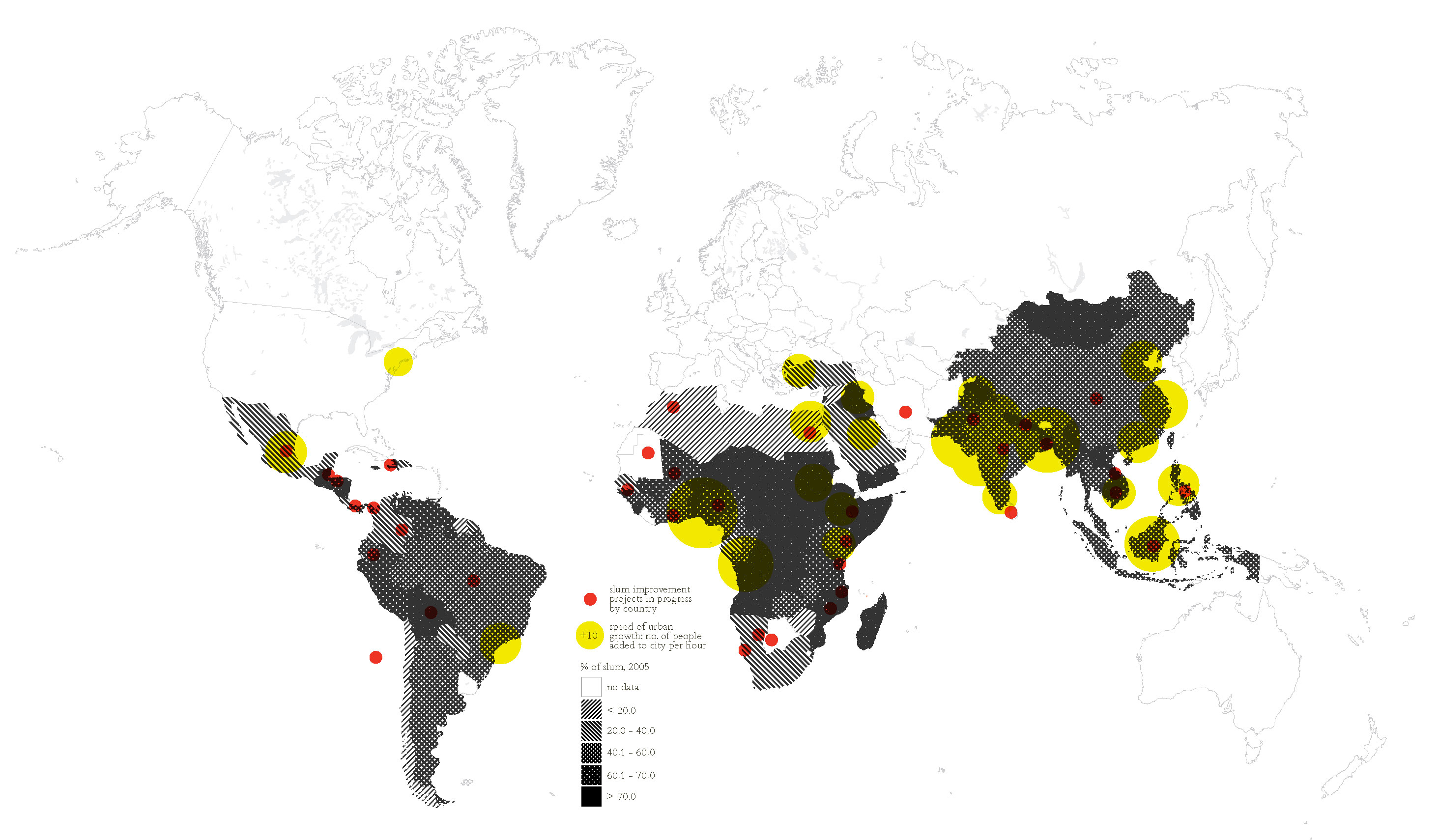

By recent estimates, we know that over 1,000,000,000 people live in informal settlements, of which the vast majority occur in developing nations. We know that 40% of populations of developing nations live in informal settlements and 70% of the world’s population will be employed by the informal sector by 2020. We also know that over 50% of the world’s population now live in cities, that 75% will be living in cities by 2050 and that 93% of all urban growth will occur in developing nations.

CHANGING PARADIGMS: A TIMELINE

1920-60

Modernism & Postwar Utopias

After the war, a new wave of optimism swept over the West with grand visons and intentions to bring in the New. To respond to the urban crises of the 19th-century industrialized cities, entirely new city plans of architectural and social engineering were deemed necessary; architects like Le Corbusier and Ebenezer Howard, believed that such new cities would not only solve the urban crises, but the social crises as well. A new, more rational and liberated human type would emerge from their totalitarian schemes; here was the seed to the belief that planners and architects had the power to bring about great social reform. This urge to instill “democratic” ideals and “liberate” the people through the determinism of social behaviour with the built environment was an immensely paradoxically utopian phenomena that manifest as a modern form of colonialism.

The New Town and the Cold War

The principles of the New Town carried over to the politics of the Cold War as East and West battled for the loyalties of developing countries; it was speculated that urban planning became an instrument of war and that it functioned as a means of cultural colonization instead of political. Greek architect, Constantin Doxiadis, leading figure of U.S. Cold War policy built new towns through the Middle East and Africa hoping to spread “democratic” values of the West in the developing world. Little to no consideration to actual ways of living in these regions meant unanticipated occupation of new cities.

1960-70

Urban Development Planning

The failings of utopian mass planning of postwar modernism gave way to a powerful anti-design discourse. The confidence in the power of architecture and urbanism of that period also meant that design practices became the main scapegoat for the failures. Proponents of this new discourse looked towards what was inimical to planning and design practices since they were unable to deal with the real city; focus was switched towards developing countries and the self-produced, unplanned, undesigned, unregulated logic of those spaces. Progressive architects and designers like John Turner, Charles Abrams, John Habraken, Giancarlo De Carlo and Team X were advocates of user participation and control in the housing process as this was perceived as the only way to produce appropriate responses to their situation. They also shared the belief that it was the social and political processes that must be examined for real change, thus, dismissing the role of the designer as insignificant and essentially unnecessary. However, the emphasis on local know-hows and ground-up approach brought about the loss of the city-scale and the networks and processes that function beyond the local level. While modernist planners placed spatialization at the forefront of effective planning practice, urban development planners did not wish to meddle with it. Space, the social, and the political were inherently tied and left to the wills of the capitalist and neo-capitalist society, with little concern for informality and poverty.

UDP & The Informal Sector

A discourse that converged with one of the most influential concepts in postwar developing countries is that of the informal economy. It is a concept that involves the production of goods, provision of services and formation of settlements, outside existing regulatory frameworks and outside the predominant forms of capitalist production. The informal represented a resourcefulness that was believed to require support and enhancement, but this could be achieved was much debated; in the majority of the developing world to this day, the informal is the dominant means of producing goods, services and cities.

UDP & Sites-and-Services Programs

By the end of the 1960’s, the focus on informality led to a search for reducing costs of programs through an extreme decrease of quality standards; this was justified by proponents under a “progressive development” concept--that is, the idea that housing and settlements were under constant flux, thus substantial investments would be in vain. The programs’ provision of basic infrastructure and sanitary measures essentially made them works of urban engineering, with spatial elements at all scale being generally overlooked.

1980 -90

SAP's & Strategic Planning

By the 1980’s, the discourse in design practices became a function of the emerging neoliberal policies of the time. This led to the onslaught of severe economic and class division. The structural adjustment programs (SAP) and neoliberal policies set out by the World Bank and IMF were meant to provide a means for developing countries to alleviate their debt crisis through the liberalization of their markets and trade. Instead, this deregulatory approach left millions of the worlds most impoverished people at risk, and without adequate protection. Housing and development policies of this period moved away from upgrading projects towards ‘strategic planning’. This discourse was aimed at establishing institutional structures to make city-building competitive in the globalized market. At this point in time, focus on the informal city became lost in the discourse and only resurfaced many years later; however, it was also at this point in time that architecture and planning disciplines were once again revalued as central tools in the process of city-making.

1990-00

Growing Poverty & New Urbanisms

The worsening conditions of poverty and socio-economic polarity in the early 1990’s, owing to neoliberal policies, were increasingly acknowledged at this time, and such policies came under strong criticism. Issues of poverty and social policy resurfaced after years of unbridled neoliberalism. New ways of understanding the conditions of poverty were emerging that emphasized its heterogeneous nature; it was now regarded as something that would need a much more integrated, multi-sectoral, multi-scalar approach in its interventions.

Housing Policies & A Resurgence of Architecture and Urbanism

As a central component to poverty reduction, housing and housing policy was once again revisted due to its now recognized associations with health, safety, income, and other significant determinants of poverty. In developing countries, housing policy became entirely associated with slum upgrading. These upgrading policies re-focused themselves to the project level (as was the case in the 70’s), but this time projects would be understood in relationship to multiple sectors, and multiple scales of interaction--socially, politically as well as spatially. With this resurgence of interest in slum upgrading also came the gradual resurgence of discussions on the role of architecture and urbansim in the realms of international agencies, institutions, academics and practitioners. In UN-Habitat’s “The Challenge of Slums” (2003) as well as their Millenium Project, acknowledgement is made to the spatial dimension of slum upgrading and the crucial contribution of the design disciplines in these issues.

2000-

Informal Urbanization: Recent Perspectives

Several new studies published in the past decade attempt to further understand informal urbanisation and its implication for design disciplines. Although varied in their analyses of its implicatios, they all share the view that the self-generated city and its merits are not simply segments of a city, but unyieldingly woven into the city as a whole and has to be seen as another way of being in the city.

"A New Epistemology"

Ananya Roy’s recent literature on urban informality is vital to the current discourse on planning practice; she argues that planning practices are inextricably tied to market economies and that the study of informality is a reminder of how “regimes of planning far exceed the acts and practices of planners” (2010, 103). Informality of the poor are “zones of exception”, but not the only exception; parallel to this form of piracy and appropriation are those of a private class who have the wealth and capacity to create a zone of exception for themselves--a “privatization of informality”. Thus, the process of the urban poor to use the law to legitimize their own land claims is a form of democratizing of urban space (2010, 101). Despite Roy’s views on the “urban catastrophe” of the 21st-century and its potential signifier as the end of planning, she hints at the hope that there may be a new, insurgent planning that draws from the methods of appropriation and resistance of the self-built democracy of the informal.

City in Motion

Paola Berenstein Jacques (2001) frames her research on informality from the aesthetics of favelas; in her view, the changing nature of the form of informal cities is a reflection of the always changing needs of the inhabitants; the informal city is characterised by a never-ending process of self-production and self-construction and this state of constant flux is, by nature, in direct conflict with the idea of planning. Informal urbanisation, thus, cannot be planned. The production of space of the informal city, determined by the needs of the users, will autonomously negotiate its way through the rest of the city. External control is rendered unnecessary as needs are being met through their own devices and continual flux cannot be planned for; not only do users therefore appropriate space, but also appropriate the role of the architect and planner. Unquestioned, however, are the driving forces which are proliferating such patterns of urban existence.

"Urbanisms of the Informal"

In Jose Castillo’s (2000) dissertation, he calls for a new way to conceptualize informal urbanization, deemed, “Urbanisms of the Informal”; these are “the practices and the forms that a group of stakeholders undertake not only to obtain access to land and housing, but also to satisfy their needs to engage in urban life” (29). He emphasizes (2001) “urbanisms” in plural, for it not only “embraces the complex and heterogeneous forms and procedures that represent these urban phenomena but also engages them both as practice and as a body of knowledge, a new episteme” (110). He argues for a shift towards this spatial framework of informality as it is a condition that remains over time. He further asserts that this new model of urbanization renders traditional modes of planning useless--attributable to its dynamic nature, the dismantling of the sequence of practice, and through the ways in which the urban hierarchies are ultimately transformed.

___

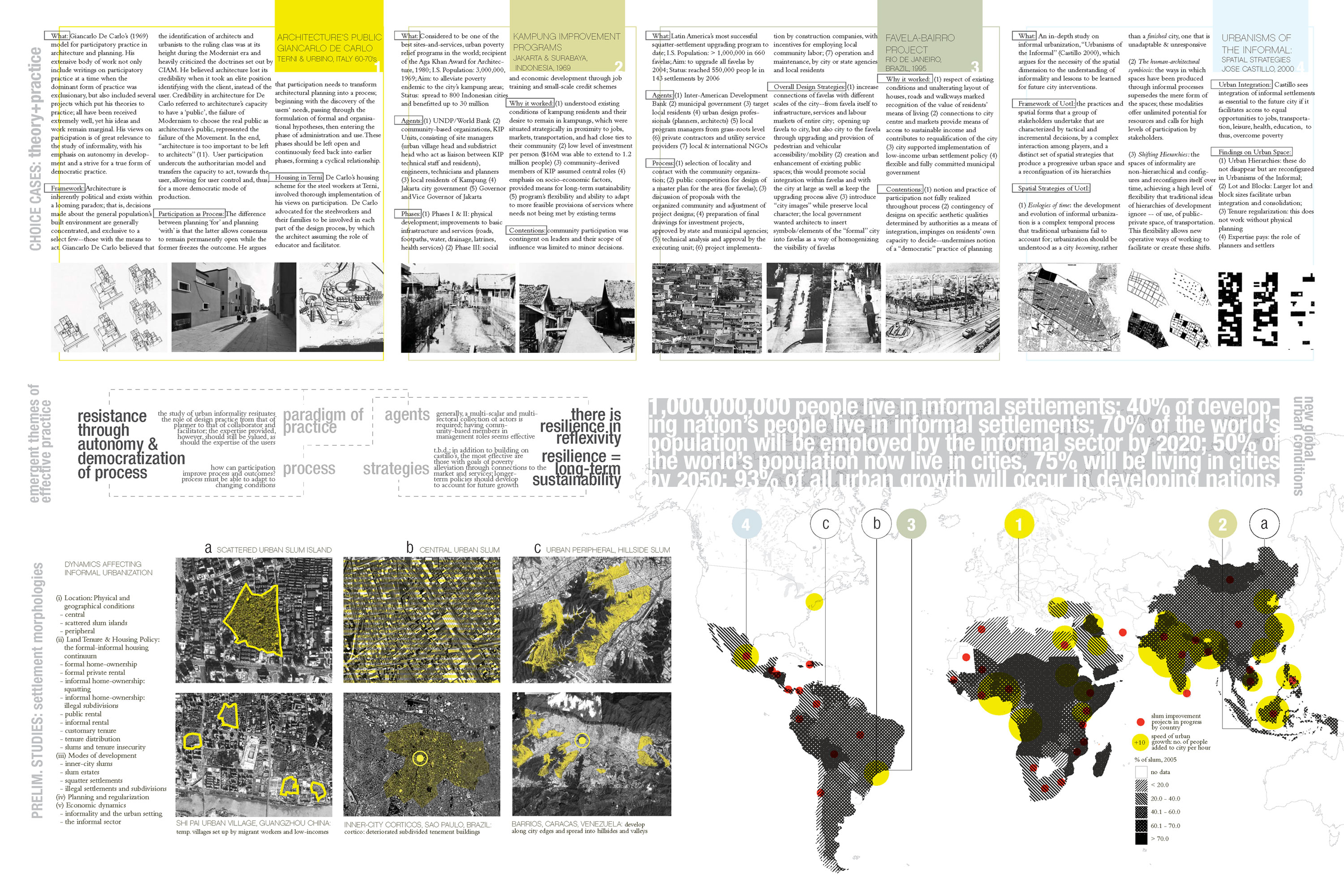

CHOICE CASES: THEORY & PRACTICE

"ARCHITECTURE’S PUBLIC"

Giancarlo De Carlo

Terni & Urbino, Italy 60-70’s

What: Giancarlo De Carlo’s (1969) model for participatory practice in architecture and planning. His extensive body of work not only include writings on participatory practice at a time when the dominant form of practice was exclusionary, but also included several projects which put his theories to practice; all have been received extremely well, yet his ideas and work remain marginal. His views on participation is of great relevance to the study of informality, with his emphasis on autonomy in development and a strive for a true form of democratic practice.

Framework: Architecture is inherently political and exists within a looming paradox; that is, decisions made about the general population’s built environment are generally concentrated, and exclusive to a select few--those with the means to act. Giancarlo De Carlo believed that the identification of architects and urbanists to the ruling class was at its height during the Modernist era and heavily criticized the doctrines set out by CIAM. He believed architecture lost its credibility when it took an elite position identifying with the client, instead of the user. Credibility in architecture for De Carlo referred to architecture’s capacity to have a ‘public’, the failure of Modernism to choose the real public as architecture’s public, represented the failure of the Movement. In the end, “architecture is too important to be left to architects” (11). User participation undercuts the authoritarian model and transfers the capacity to act, towards the user, allowing for user control and, thus, for a more democratic mode of production.

Participation as Process: The difference between planning ‘for’ and planning ‘with’ is that the latter allows consensus to remain permanently open while the former freezes the outcome. He argues that participation needs to transform architectural planning into a process; beginning with the discovery of the users‘ needs, passing through the formulation of formal and organisational hypotheses, then entering the phase of administration and use. These phases should be left open and continuously feed back into earlier phases, forming a cyclical relationship.

Housing in Terni: De Carlo’s housing scheme for the steel workers at Terni, involved thorough implementation of his views on participation. De Carlo advocated for the steelworkers and their families to be involved in each part of the design process to which the architect assumed the role of educator and facilitator.

"FAVELA-BAIRRO PROJECT"

Favela Upgrading Program

Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, 1995

What: Latin America’s most successful squatter-settlement upgrading program to date; I.S. Population: > 1,000,000 in 660 favelas; Aim: to upgrade all favelas by 2004; Status: reached 550,000 peop le in 143 settlements by 2006

Agents: (1) Inter-American Development Bank (2) municipal government (3) target local residents (4) urban design professionals (planners, architects) (5) local program managers from grass-roots level (6) private contractors and utility service providers (7) local & international NGOs

Process: (1) selection of locality and contact with the community organization; (2) public competition for design of a master plan for the area (for favelas); (3) discussion of proposals with the organized community and adjustment of project designs; (4) preparation of final drawings for investment projects, approved by state and municipal agencies; (5) technical analysis and approval by the executing unit; (6) project implementation by construction companies, with incentives for employing local community labor; (7) operation and maintenance, by city or state agencies and local residents

Overall Design Strategies: (1) increase connections of favelas with different scales of the city--from favela itself to infrastructure, services and labour markets of entire city; opening up favela to city, but also city to the favela through upgrading and provision of pedestrian and vehicular accessibility/mobility (2) creation and enhancement of existing public spaces; this would promote social integration within favelas and with the city at large as well as keep the upgrading process alive (3) introduce “city images” while preserve local character; the local government wanted architects to insert symbols/elements of the “formal” city into favelas as a way of homogenizing the visibility of favelas

Why it worked: (1) respect of existing conditions and unalterating layout of houses, roads and walkways marked recognition of the value of residents’ means of living (2) connections to city centre and markets provide means of access to sustainable income and contributes to requalification of the city (3) city supported implementation of low-income urban settlement policy (4) flexible and fully committed municipal government

Contentions: (1) notion and practice of participation not fully realized throughout process (2) contingency of designs on specific aesthetic qualities determined by authorities as a means of integration, impinges on residents’ own capacity to decide--undermines notion of a “democratic” practice of planning

"URBANISMS OF THE INFORMAL"

Spatial Strategies

Jose Castillo, 2000

What: An in-depth study on informal urbanization, “Urbanisms of the Informal” (Castillo 2000), which argues for the necessity of the spatial dimension to the understanding of informality and lessons to be learned for future city interventions.

Framework: the practices and spatial forms that a group of stakeholders undertake that are characterized by tactical and incremental decisions, by a complex interaction among players, and a distinct set of spatial strategies that produce a progressive urban space and a reconfiguation of its hierarchies

Spatial Strategies:

(1) Ecologies of time: the development and evolution of informal urbanization is a complex temporal process that traditional urbanisms fail to account for; urbanization should be understood as a city becoming, rather than a finished city, one that is unadaptable & unresponsive

(2) The human-architectural symbiosis: the ways in which spaces have been produced through informal processes supersedes the mere form of the spaces; these modalities offer unlimited potential for resources and calls for high levels of participation by stakeholders.

(3) Shifting Hierarchies: the spaces of informality are non-hierarchical and configures and reconfigures itself over time, achieving a high level of flexibility that traditional ideas of hierarchies of development ignore -- of use, of public-private space, of transportation. This flexibility allows new operative ways of working to facilitate or create these shifts.

Urban Integration: Castillo sees integration of informal settlements as essential to the future city if it facilitates access to equal opportunities to jobs, transportation, leisure, health, education, to thus, overcome poverty

Findings on Urban Space:

(1) Urban Hierarchies: These do not disappear but are reconfigured in Urbanisms of the Informal (2) Lot and Blocks: Larger lot and block sizes facilitate urban integration and consolidation (3) Tenure regularization: This does not work without physical planning (4) Expertise pays: The role of planners and settlers as experts in their own way

Text and layout by Olivia Cheung

1-3 - Informal Urbanism & Poverty (Olivia Cheung, 2011)

4 - Kowloon Walled City (Greg Girard, 1987)

Sources

Felipe Hernández, Peter William Kellett, Lea K. Allen. Rethinking the Informal City: Critical Perspectives from Latin America. Berghahn Books: 2010.

Jose Manuel Castillo. Urbanisms of the Informal: Spatial transformations in the urban fringe of Mexico City. Dissertation for Harvard Design School, June 2000.

Ananya Roy and Nezar Alsayyad (Eds). Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia. Lexington Books: 2004.

Ananya Roy. “Informality and the Politics of Planning” in The Ashgate Research Companion to Planning Theory: Conceptual Challenges for Spatial Planning. J. Hillier and P. Healey, eds. Ashgate: 2010.

Giancarlo De Carlo. 'Architecture's Public', in Architecture and Participation, ed. by Peter Blundell Jones, Doina Petrescu and Jeremy Till. Abingdon: Spon Press: 2007.

United Nations Human Settlements Programme. The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements 2003. UN-HABITAT: 2003.