(02 Rubber Soul)

Rubber Soul

What — In our modern urban conditions, how do we navigate between the notions of preserving our self-identities and of being receptive to our social and material environments? Does one necessitate the exclusion of the other? ( M.Arch. Thesis, 2012)

We see that the self-preservation of certain types of personalities is obtained at the cost of devaluing the entire objective world, ending inevitably in dragging the personality downward into a feeling of its own valuelessness.

– G. Simmel (The Metropolis and Mental Life, 1903)

That which is not slightly distorted lacks sensible appeal; from which it follows that irregularity – that is to say, the unexpected, surprise and astonishment, are a essential part and characteristic of beauty.

– C. Baudelaire

Modern Mechanisms of Protection

As inhabitants of the modern urban condition, we have increasingly been driven to rely on cognitive, spatial and technological protective mechanisms that are creating new forms of social life. Written in 1903, sociologist Georg Simmel’s seminal text, “The Metropolis and Mental Life”, is increasingly relevant today. The city and its social life, in his view, became functions of the capitalist economy, in which all of our interactions had been reduced to the quantifiable. All that was qualitative in our exchanges had lost its value, and had been replaced with principles of efficiency, rationality and productivity. Combined with the immense intensification of sensory stimuli and disruptions we are confronted with, we find ourselves struggling to navigate between the preservation of our self-identities while still being receptive to our social and material environments. Simmel states, "...the metropolitan type – which naturally takes on a thousand individual modifications – creates a protective organ for itself against the profound disruption with which the fluctuations and discontinuities of the external milieu threaten it" (12).

In “Spheres Volume III: Foam” (2011), Peter Sloterdijk observes another form of protection. He speaks of our desire to seek intensified forms of interiority driven by the profound fear of biosocial threats in our environment, and in specific, the air we breathe. Ever since it has been brought to the scientific foreground, it has become an object that we must now manage. This new awareness of things that were always there is the process of explication. And indeed with this explication and the onset of technological and scientific advancements, we have developed increasingly sophisticated ways to manufacture air, to use technology to protect ourselves and our existence. Technologies of habitation have now had to transform; he analogizes the modern apartment to a spatial immune system in that immunity is "...a measure of defense through which a zone of well-being is walled off against invaders and other bearers of illness. All immune systems go beyond reason in calling upon their right to defend against disruptions" (534). Thus, the new urban ideology has easily become: to protect our self, we must live to the exclusion of others.

A Corporeal, Instinctive Response

Should we continue on this trajectory towards interiorizing existence and self-exclusion from the environment? Or can we find ways to sustain our connection to the external world? Our project conceives of cognitive-spatial ideas that act to retrieve our instinctual, emotive responses at given urban opportunities, in a way that engages our corporeal beings with the environment. We are attempting to begin the restoration of balance to our individualizing ways of life without denying the realities of urban existence.

What better way to explore these ideas than with rubber material. We are using rubber for its haptic and responsive qualities, in a way that can cut the existing tension between “safe” interior and “invasive” exterior, between the rational mind and our sentient being. The project situates itself within corporate urbanisms – a contributing force to our blasé state of being and we are using rubber as an interface replacing the modern conventions of floor, wall and roof. Through it’s defining properties, we explore its ability to respond to human touch and environmental conditions, and how this might trigger affiliative instinctual behaviours like curiosity, play and sociability.

Material + Methods

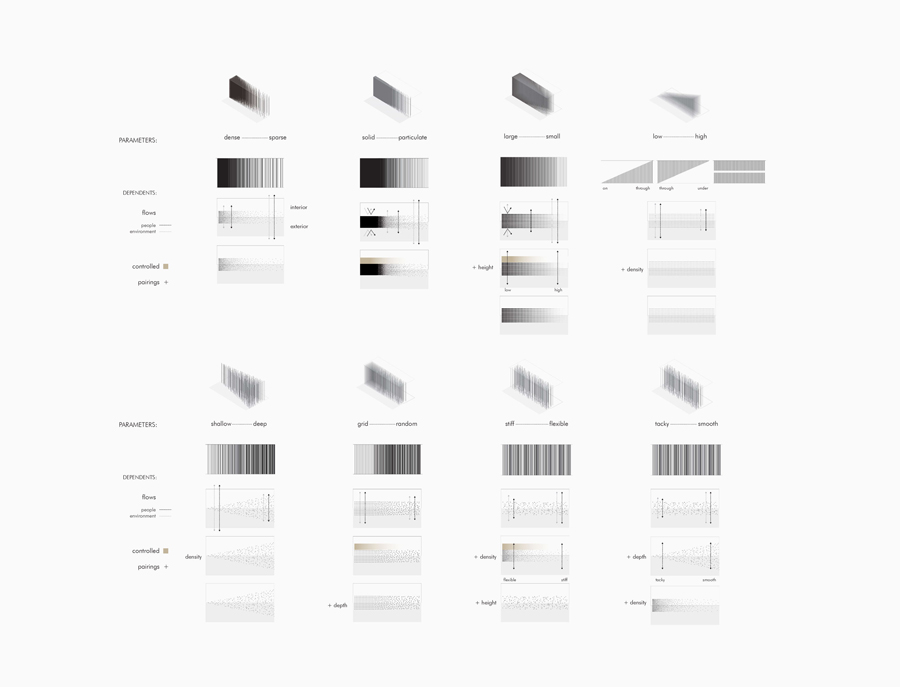

We saw the process of exploring the material we would be working with as integral to how we would conceive of the designs. We used a two-part liquid-based curing process for each type of rubber (latex, polyurethane and silicone). Stretch, bounce, softness, transparency, texture and tackiness were the main variables we aimed to control for. The resultant rubber formations that had the most potential fit into three types: "sheets", "tear drops" and "drips". Sheet and tear drop models were fabricated through the casting of rubber in cnc-milled foam molds, while drips were made by pouring low-viscosity rubber through punctured surfaces (created by laser cutting sheets of acrylic).

Case Typology: Sheets

The idea of the sheet was developed as an interesting substitute for the conventional solid surfaces of our floors, walls and roofs. Its formal resemblance to these conventions can add an element of the unexpected through its behavior. It can seem like a form of enclosure, while still maintaining the ability to respond to exterior conditions like wind, snow and rain. In one scenario, a rubber roof is designed to collect precipitation, and based on the weight of precipitation, wide rubber drops can fall to just above you or can become tear drops as they stretch down towards the floor and substantially interrupt the space. The wide rubber drops can furthermore be punctured in ways that allow for snow or water to penetrate into the space: As mist, all of your senses are demanded to kick in as you try to find your way; as a spinkle, you look up in curiosity or slip on the puddle that has been forming below; as a shower, you run for cover, immerse yourself in the shower, or navigate around the moments of falling water in the space. The resulting experience may be playful, uncomfortable or sublime; yet in all instances you are aware of your surroundings in the moment, as your body and senses become engaged.