(01 Toilet Politics)

Toilet Taboos, Politics & Revolution

Below, an original copy written as an opening essay for a book with a focus on the design of public restrooms and contemporary case studies. The published version was a rewritten piece to accommodate the purposes of the book, found here.

The public restroom has been fertile grounds for contention, revolution and civil transformation. It may initially be an absurd notion to consider the power of the public toilet, but a quick look back in history reveals stories steeped in civil turbulence and themes of social equality and inclusivity. Even today, the contention of public toilets in terms of equal access and the acute lack of public restrooms in countries around the world, can be found making headlines. This is revelatory in understanding the depths to which toilet taboos go and questions what can be done by designers to challenge these ingrained concepts.

From the earliest form of the toilet, restroom design and technologies have undergone numerous iterations, from the “pig toilets” in ancient China to hands-free, self-cleaning washrooms today. The most comprehensive study of washroom design to date is architect Alexander Kira’s book The Bathroom, released in 1966, a landmark study conducted at Cornell University over a seven-year period. Through laboratory testing, fieldwork and cultural analysis, it was the first of its kind to consider the varying needs of different user groups from the lens of use and product production. This user-centered approach of restroom design became the standard for design professionals and was the precursor for the inception of ‘universal design’ standards.

Toilet Politics, Access and Inclusivity

“Inclusive bathrooms enable a ‘maximum number of persons to participate fully in public life’” - Judith Plaskow

“As soon as you flush the toilet, you’re in the middle of ideology” - Slavoj Žižek

The idea and practice that a public restroom should be available to anyone in need, is an astoundingly recent invention. When it comes to gender, race, economic status and people with disabilities, the design and application of equal access laws for public restroom facilities was, and still is in some cases, a difficult road towards justice for those excluded by the dominant group; exclusionary toilet practices was both a reflection and incitement of the exclusion of these social groups from the public realm—the link between access to inclusive restrooms and the ability to participate in public life is strong.

Up until the Industrial Revolution, public restrooms and facilities were for men only—a woman’s place was intended for the domestic sphere. The lack of women’s restrooms kept women on a “urinary leash”, controlling the time spent in public and places they could go. Change did not emerge until the early 20th century when women finally joined the workforce and developed some financial and social mobility. London’s Great Exhibition in 1851 finally introduced a women’s-only public restroom, but not until UK’s suffragette movement and other campaigns for women’s rights in the late 1800s did public toilet use for women become more widely accepted in the West.

Today, gender issues continue to generate public discord. Most countries in the world still provide more public restrooms for men than women when women need it most. Women in developing countries such as India have been particularly vulnerable without proper provisions for public or private facilities. Also at risk are transgender individuals who fear harassment in public toilet facilities; in 2016, North Carolina passed a ‘bathroom bill’ that required transgender people to use public restrooms based on their gender assigned at birth, causing many in the transgender community to avoid public restrooms all together. In 2017, the bill was partially repealed due to the lobbying of human rights and LGBT groups.

Also entangled in their fight for civil rights, the African American population fought profoundly discriminatory laws laid against them, largely in the southern states after the Civil War, that involved equal access to public institutions and facilities. Racial segregation, institutionalized by the Jim Crow laws, meant that African Americans were forced to use “for colored-only” restroom facilities in public institutions or none at all. In the words of African American legal scholar Taunya Lovell Banks, “perhaps only people who have been denied access by law to bathrooms can fully understand the impact both on body and dignity of this form of discrimination.” This institutionalized racism severely limited their participation and mobility in the public realm, and lasted for almost a century up until the eventually hard-won enactment of the Civil Rights Act in the mid-1960s.

By these accounts, the power of the toilet is evident: its provision and use has had the capacity to reflect a society’s dominant political and cultural ideologies, and was often a means to actively assert them. Professor Barbara Penner, author of Bathroom, states, “an inclusive bathroom is a space that does not exclude particular user groups either by design or by law: rather, it positively promotes mobility and well-being. An inclusive bathroom is a necessary component of a socially just society.”

Around the time of the civil rights movement, another group’s campaign for equal access was gaining momentum and has since become the most influential and successful crusade in the reformation of public restroom design. In 1961, the world’s first access standard was introduced: the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) issued the A117.1 standard which mandated that public buildings and facilities should be made accessible to people with disabilities. Sweden and Denmark took the lead in championing the accessibility movement at the time, as well as scholars and architects like Ted Nugent, who devised the draft for the A117.1, and Selwyn Goldsmith, who wrote the significant, Designing for the Disabled, in 1963. By the 1970s, the needs of this group were increasingly being acknowledged and provided for in architecture and design manuals and in the marketplace; more accessible bathroom equipment was finally being designed, manufactured and disseminated for non-standard users.

Human-centered & Universal Design

The new access laws had finally given voice and public mobility to a once marginalized segment of the population. The provision of special facilities to meet the requirements for people with disabilities was a positive step towards inclusivity. Around the time that the accessibility movement was taking shape, a more encompassing approach to inclusive design and equal access was also underway: universal design. If design for people with disabilities is the provision of specialized facilities in order to include a specific user group, universal design seeks to make regular facilities accessible by all people regardless of age, size, culture, ability or disability. Also considered are health issues and safety features such as non-slip surfaces and ergonomic toilets. Universal design, thus, de-standardizes the user—the user that had been based on averages since the mid-1800s.

During the mid-1800s, public restroom design was mostly driven by the sanitary product industry which relied on standardized data in order to produce cost-effective, space efficient and durable restrooms. Standardization of the user was seen as one answer to large-scale health and hygiene issues, but it meant that outliers would certainly be excluded and human factors such as anatomy and behavior would, on the most part, be overlooked. When architects did involve themselves in bathroom design, they often relied on graphic standards guides that originated from American military research, privileging the average caucasian, able-bodied young man. At least ten percent of the population would not be able to access standardized public restrooms.

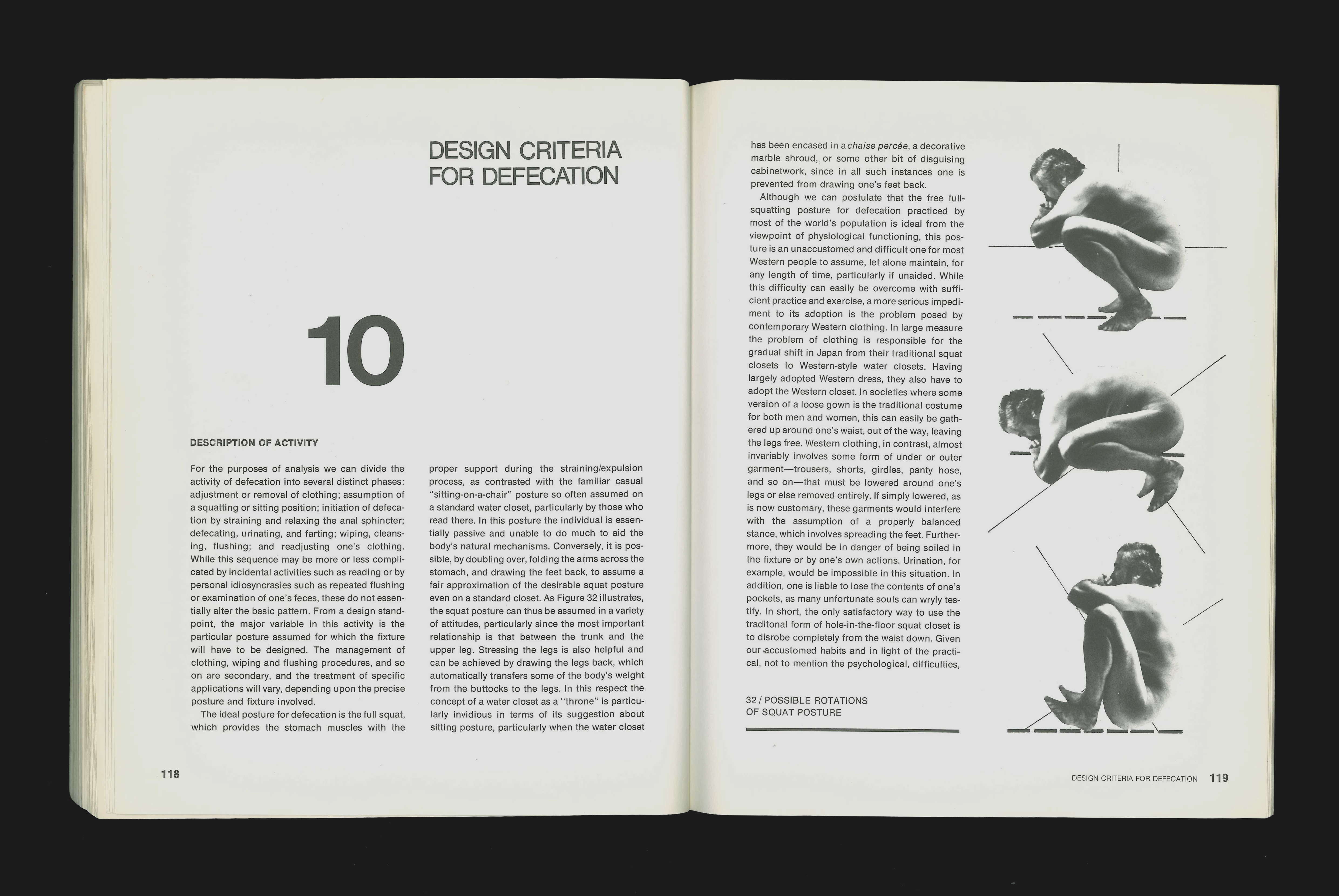

Design based on the standardized user was a staple through the high modernist period in architecture; Le Corbusier’s catch phrase after all was : “Standard functions, standard needs, standard objects, standard dimensions.” When it came to the bathroom, these sentiments were challenged in a seminal study at the time of high modernism, conducted by a Cornell University professor in architecture, Alexander Kira. He presents his findings in The Bathroom, one of the most comprehensive books on bathroom design, first published in 1966. Over a seven-year period, an interdisciplinary team of researchers performed laboratory work, fieldwork and cultural analysis, to produce a detailed set of design criteria for the bathroom based on human anatomy, anthropometric data and behavior. Kira’s findings were based in the understanding that the age, size and ability of users would vary and users themselves would undergo changes in their lifetime (such as illnesses and pregnancies) and developed adaptable features for bathroom fittings to accommodate this. While the findings were thorough and revelatory (for instance, he discovered optimal heights and dimensions for bathroom activities and fittings differed from those in the Architectural Graphic Standards), this human-centered approach, which advocated for ergonomic fittings like the semi-squat toilet and safety bars to be normalized, initially received resistance by producers and consumers of the time; social and cultural attitudes to a taboo subject were not easy to reform.

Alexander Kira’s wonderfully meticulous and witty book was a groundbreaking force in the battle to dismantle toilet taboos and in the development of universal design. Today, universal design has become more widely used in the design of public restrooms; it simply mandates that architecture should not discriminate against any user.

Toilet Taboos, Architecture & Revolution

While universal design may set the scene for the greatest number of people to use a space, whether or not users will indeed use such public restrooms is inherently psychological by nature; by all accounts, the act of elimination is a private act. Nick Haslam, author of Psychology in the Bathroom, explains that we are socialized from an early age to attach shame and secrecy to the bathroom, and that it could stem from evolution and instinct: “Another reason for the taboo is perhaps an entirely adaptive and evolved aversion to bodily waste, which is linked to disease and contamination. To some degree there will always be some anxiety and disgust attached to excretion for this reason.” It follows then that in architecture, the public restroom is a space in which the tension between public and private is at its height. How we account for this in restroom design becomes significant in order to have optimal utilization.

In the architectural sphere today, public bathroom design is beginning to break through toilet taboos, and the issues of privacy, access and inclusion and user-centered design, should no longer be central to the conversation. As we witness in the exceptional projects in this book, perhaps the answer to tackling toilet taboos is simple: design the public restroom as if it is not a taboo; bring it the foreground and place the same amount of reverence and care into its design as one would to any another monument of architecture. Fundamental to our experience of great architecture, when we are moved by a space, when we witness care through its details, materiality, craftsmanship, the orchestration of space, light and experience, we in turn, ultimately honor and place value on it as well. The more we experience thoughtfully-designed public bathrooms, the more we will come to respect it, and the less we will fear it. Understanding the presence of this reciprocal relationship and studying these projects can inspire a new, higher standard for public bathroom design.

The beauty and spirit of the collection of projects in this book make an crucial statement that public restrooms matter. While gender, race, lack of provision and other socio-political issues still occupy much of the public toilet discourse today, it is encouraging to see how models of investment into quality public restrooms can result. These examples fully embody the notions of social justice and the importance of the provision of quality public facilities for all, yet they also launch new conversations on how public toilet design can be pushed further. Examples of environmental sustainability, innovative technologies, the integration and relationship to landscape and art, and culture, abound in these projects. They point towards a revolution in public restroom design, one in which the social and historical significance of the public restroom is manifest through the celebration of its design and architecture. Since we have observed that bathrooms are culturally and historically specific, the existence of these projects today reflects a hopeful transition in our social and cultural attitudes; it reflects the importance we place on public restrooms, public facilities and in turn on public life in the sustainment of healthy and inclusive communities, cities and societies at large.

References

1. Bathroom by Barbara Penner, 2013. Reaktion Books Ltd, London.

2. The Bathroom by Alexander Kira, 1966, 1976. The Viking Press, Inc. New York.

3. Toilet by Harvey Molotch & Laura Noren. NYU Press, New York. 2010.

4. Entangled with a User: Inside Bathrooms with Alexander Kira and Peter Greenaway. In Toilet by Harvey Molotch & Laura Noren. NYU Press, New York. 2010. Pp. 229-252.

5. Pissing without Pity: Disability, Gender, and the Public Toilet. In Toilet by Harvey Molotch & Laura Noren. NYU Press, New York. 2010. Pp. 167-185.

6. Toilet Psychology by Nick Haslam. June 2012, Vol 25 No 6. The Psychologist. https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-25/edition-6/toilet-psychology

7. How the psychology of public bathrooms explains the 'bathroom bills' by Nick Haslam, May 13, 2016. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2016/05/13/how-the-psychology-of-public-bathrooms-explains-the-bathroom-bills/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.eda46cb6096f

8. The Private Lives of Public Bathrooms. By Julie Beck, April 16, 2014. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/04/the-private-lives-of-public-bathrooms/360497/

9. Typology: Public toilet. By Tom Wilkinson. The Architectural Review, November 29, 2017. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/typology/typology-public-toilet/10025687.article

10. A brief history of the ladies' bathroom. Therese Oneill. May 12, 2016. The Week. http://theweek.com/articles/621109/brief-history-ladies-bathroom

11. Everything We Know About Human Bathroom Behavior. Clint Rainey. May 4, 2015. The Cut, New York Magazine. https://www.thecut.com/2015/05/science-of-us-guide-to-bathroom-behavior.html